Useful one-function R packages, big data solutions, and a message from Yoda

Abstract

As the title reads, in this heterogeneous session we will see three topics of different interest. The first is a collection of three simple and useful one-function R packages that I use regularly in my coding workflow. The second collects some approaches to handling and performing linear regression with big data. The third brings in the freaky component: it presents tools to display graphical information in plain ASCII, from bivariate contours to messages from Yoda!

You can download the script with the R code alone here (right click and “Save as…”).

Required packages

We will need the following packages:

install.packages(c("viridis", "microbenchmark", "multcomp", "manipulate",

"ffbase", "biglm", "leaps", "txtplot", "NostalgiR",

"cowsay"),

dependencies = TRUE)Some simple and useful R packages

Color palettes with viridis

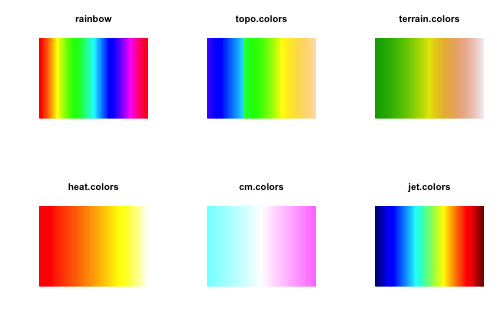

Built-in color palettes in base R are somehow limited. We have rainbow, topo.colors, terrain.colors, heat.colors, and cm.colors. We also have flexibility to create our own palettes, e.g. by using colorRamp. These palettes look like:

# MATLAB's color palette

jet.colors <- colorRampPalette(c("#00007F", "blue", "#007FFF", "cyan",

"#7FFF7F", "yellow", "#FF7F00", "red",

"#7F0000"))

# Plot for palettes

testPalette <- function(col, n = 200, ...) {

image(1:n, 1, as.matrix(1:n), col = get(col)(n = n, ...),

main = col, xlab = "", ylab = "", axes = FALSE)

}

# Color palettes comparison

par(mfrow = c(2, 3))

res <- sapply(c("rainbow", "topo.colors", "terrain.colors",

"heat.colors", "cm.colors", "jet.colors"), testPalette)

Notice that some palettes clearly show non-uniformity in the color gradient. This potentially leads to an interpretation bias when inspecting heatmaps colored by these scales: some features are (unfairly) weakened and others are (unfairly) strengthen. This distortion on the representation of the data can be quite misleading.

In addition to these problems, some problematic points that are not usually thought when choosing a color scale are:

- How does your pretty color image look like when you print it in black-and-white?

- How do colorblind people read the images?

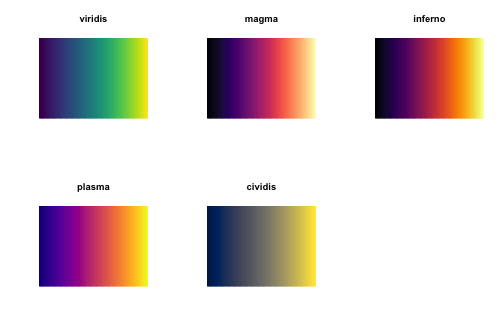

The package viridisLite (a port from Python’s Matplotlib) comes to solve these three issues. It provides the viridis color palette, which uses notions from color theory to be as much uniform as possible, black-and-white-ready, and colorblind-friendly. From viridisLite’s help:

This color map is designed in such a way that it will analytically be perfectly perceptually-uniform, both in regular form and also when converted to black-and-white. It is also designed to be perceived by readers with the most common form of color blindness.

More details can be found in this great talk by one of the authors:

There are several palettes in the package. All of them have the same properties as viridis (i.e., perceptually-uniform, black-and-white-ready, and colorblind-friendly). The cividis is specifically aimed to people with color vision deficiency. Let’s see them in action:

library(viridisLite)

# Color palettes comparison

par(mfrow = c(2, 3))

res <- sapply(c("viridis", "magma", "inferno", "plasma", "cividis"),

testPalette)

Some useful options for any of the palettes are:

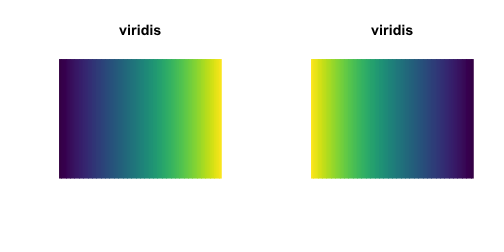

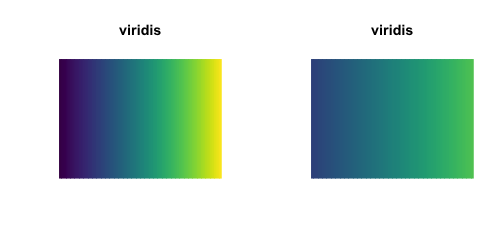

# Reverse palette

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

testPalette("viridis", direction = 1)

testPalette("viridis", direction = -1)

# Truncate color range

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

testPalette("viridis", begin = 0, end = 1)

testPalette("viridis", begin = 0.25, end = 0.75)

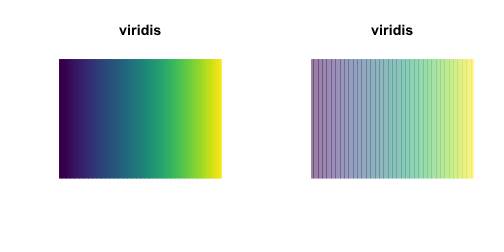

# Asjust transparency

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

testPalette("viridis", alpha = 1)

testPalette("viridis", alpha = 0.5)

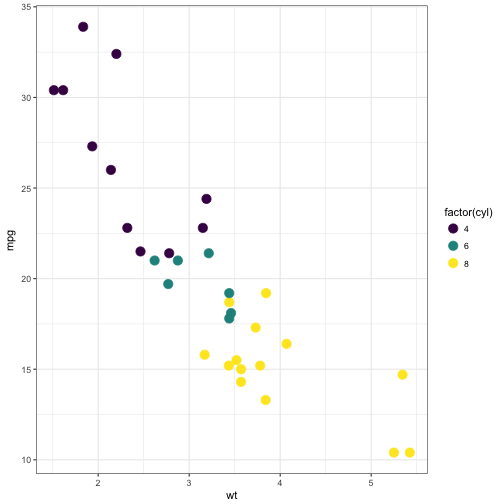

In the extended viridis package there are color palettes functions for ggplot2 fans: scale_color_viridis and scale_fill_viridis. Some examples of their use:

library(viridis)

library(ggplot2)

# Using scale_color_viridis

ggplot(mtcars, aes(wt, mpg)) +

geom_point(size = 4, aes(color = factor(cyl))) +

scale_color_viridis(discrete = TRUE) +

theme_bw()

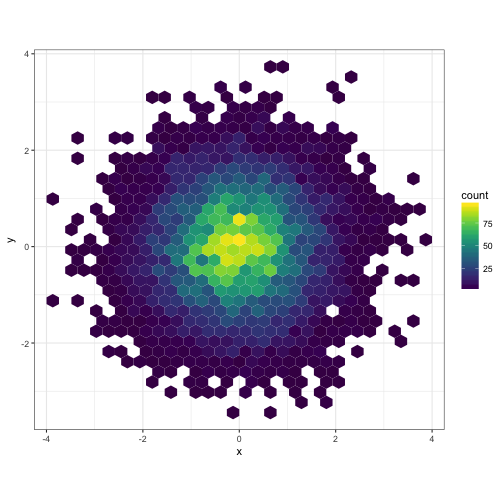

# Using scale_fill_viridis

dat <- data.frame(x = rnorm(1e4), y = rnorm(1e4))

ggplot(dat, aes(x = x, y = y)) +

geom_hex() + coord_fixed() +

scale_fill_viridis() + theme_bw()

Benchmarking with microbenchmark

Measuring the code performance is a day-to-day routine for many developers. It is also a requirement for regular users that want to choose the most efficient coding strategy for implementing a method.

As we know, we can measure running times in base R using proc.time or system.time:

# Using proc.time

time <- proc.time()

for (i in 1:100) rnorm(100)

time <- proc.time() - time

time # elapsed is the 'real' elapsed time since the process was started## user system elapsed

## 0.004 0.000 0.003# Using system.time - a wrapper for the above code

system.time({for (i in 1:100) rnorm(100)})## user system elapsed

## 0.003 0.000 0.003However, this very basic approach presents several inconveniences to be aware of:

- The precision of

proc.timeis within the millisecond. This means that evaluating1:1000000(usually) takes0seconds at the sight ofproc.time. - Each time measurement of a procedure is subjected to variability (depends on the processor usage at that time, processor warm-up, memory status, etc). So, one single call is not enough to assess the time performance, several must be made (conveniently) and averaged.

- It is cumbersome to check the times for different expressions. We will need several lines of code for each and creating auxiliary variables.

- There is no summary of the timings. We have to code it by ourselves.

- There is no checking on the equality of the results outputted from different approaches (accuracy is also important, not only speed!). Again, we have to code it by ourselves.

Hopefully, the microbenchmark package fills in these gaps. Let’s see an example of its usage on approaching a common problem in R: how to recentre a matrix by columns, i.e., how to make each column to have zero mean. There are several possibilities to do so, with different efficiencies.

# Data and mean

n <- 3

m <- 10

X <- matrix(1:(n * m), nrow = n, ncol = m)

mu <- colMeans(X)

# We assume mu is given in the time comparisonsTime to think by yourself on the competing approaches! Do not cheat and do not look into the next chunk of code!

# SPOILER ALERT!

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

# Some approaches:

# 1) sweep

Y1 <- sweep(x = X, MARGIN = 2, STATS = mu, FUN = "-")

# 2) apply (+ transpose to maintain the arrangement of X)

Y2 <- t(apply(X, 1, function(x) x - mu))

# 3) scale

Y3 <- scale(X, center = mu, scale = FALSE)

# 4) loop

Y4 <- matrix(0, nrow = n, ncol = m)

for (j in 1:m) Y4[, j] <- X[, j] - mu[j]

# 5) magic (my favourite!)

Y5 <- t(t(X) - mu)Which one do you think is faster? Do not cheat and answer before seeing the output of the next chunk of code!

# Test speed

library(microbenchmark)

bench <- microbenchmark(

sweep(x = X, MARGIN = 2, STATS = mu, FUN = "-"),

t(apply(X, 1, function(x) x - mu)),

scale(X, center = mu, scale = FALSE),

{for (j in 1:m) Y4[, j] <- X[, j] - mu[j]; Y4},

t(t(X) - mu)

)

# Printing a microbenchmark object gives a numerical summary

bench## Unit: microseconds

## expr min

## sweep(x = X, MARGIN = 2, STATS = mu, FUN = "-") 27.106

## t(apply(X, 1, function(x) x - mu)) 25.869

## scale(X, center = mu, scale = FALSE) 30.546

## { for (j in 1:m) Y4[, j] <- X[, j] - mu[j] Y4 } 1809.293

## t(t(X) - mu) 5.475

## lq mean median uq max neval cld

## 32.5985 40.74705 36.8545 46.6620 125.168 100 a

## 33.0635 51.26332 40.1875 46.9645 1108.167 100 a

## 41.5115 52.32801 50.6105 60.4620 132.956 100 a

## 1980.4605 2308.61451 2111.5060 2267.6455 16728.332 100 b

## 6.8630 9.68068 8.4820 11.5620 26.314 100 a# Notice the last column. It is only present if the package multcomp is present.

# It provides a statistical ranking (accounts for which method is significantly

# slower or faster) using multcomp::cld

# Adjusting display

print(bench, unit = "ms", signif = 2)## Unit: milliseconds

## expr min lq

## sweep(x = X, MARGIN = 2, STATS = mu, FUN = "-") 0.0270 0.0330

## t(apply(X, 1, function(x) x - mu)) 0.0260 0.0330

## scale(X, center = mu, scale = FALSE) 0.0310 0.0420

## { for (j in 1:m) Y4[, j] <- X[, j] - mu[j] Y4 } 1.8000 2.0000

## t(t(X) - mu) 0.0055 0.0069

## mean median uq max neval cld

## 0.0410 0.0370 0.047 0.130 100 a

## 0.0510 0.0400 0.047 1.100 100 a

## 0.0520 0.0510 0.060 0.130 100 a

## 2.3000 2.1000 2.300 17.000 100 b

## 0.0097 0.0085 0.012 0.026 100 a# unit = "ns" (nanosecs), "us" ("microsecs"), "ms" (millisecs), "s" (secs)

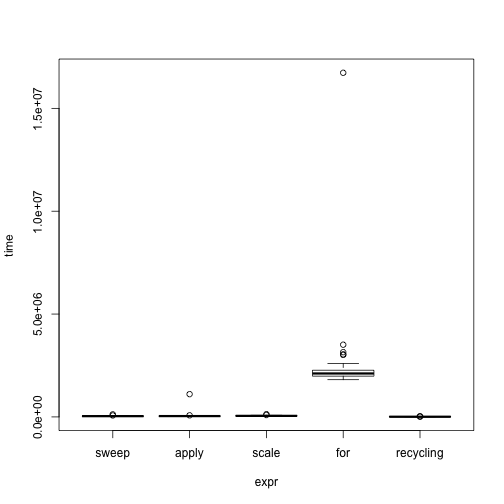

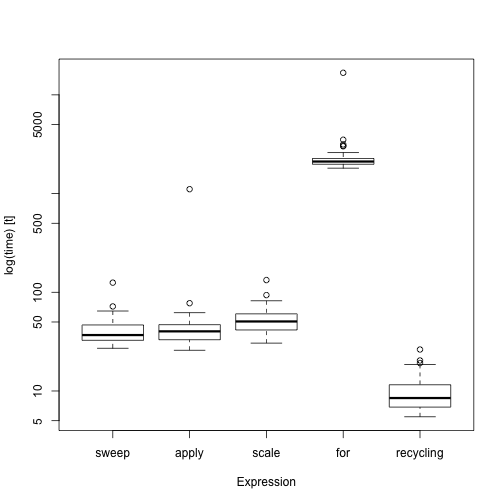

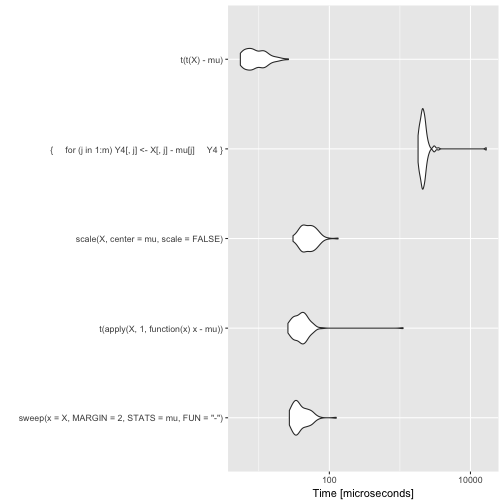

# Graphical methods for the microbenchmark object

# Raw time data

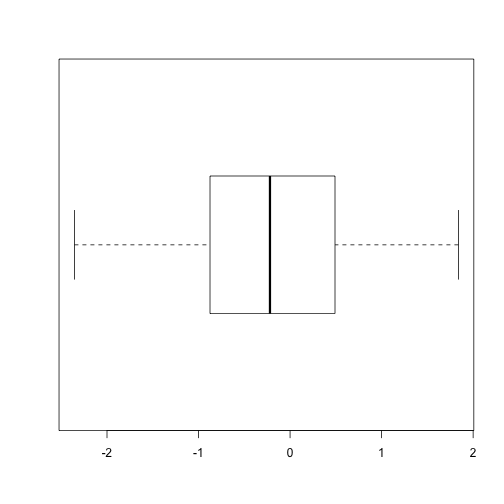

par(mfrow = c(1, 1))

plot(bench, names = c("sweep", "apply", "scale", "for", "recycling"))

# Employs time logarithms

boxplot(bench, names = c("sweep", "apply", "scale", "for", "recycling"))

# Violin plots

autoplot(bench)

# microbenchmark uses 100 evaluations and 2 warmup evaluations (these are not

# measured) by default. Here is how to change these dafaults:

bench2 <- microbenchmark(

sweep(x = X, MARGIN = 2, STATS = mu, FUN = "-"),

t(apply(X, 1, function(x) x - mu)),

scale(X, center = mu, scale = FALSE),

{for (j in 1:m) Y4[, j] <- X[, j] - mu[j]; Y4},

t(t(X) - mu),

times = 1000, control = list(warmup = 10)

)

bench2## Unit: microseconds

## expr min

## sweep(x = X, MARGIN = 2, STATS = mu, FUN = "-") 23.904

## t(apply(X, 1, function(x) x - mu)) 22.755

## scale(X, center = mu, scale = FALSE) 29.752

## { for (j in 1:m) Y4[, j] <- X[, j] - mu[j] Y4 } 1793.779

## t(t(X) - mu) 5.174

## lq mean median uq max neval cld

## 30.0340 56.16524 35.3675 48.0395 14865.043 1000 a

## 29.8515 57.46285 37.8070 48.4140 14370.849 1000 a

## 38.2395 53.72270 49.1660 64.1840 137.962 1000 a

## 1982.3630 2368.55977 2101.0770 2276.9325 20275.055 1000 b

## 7.1435 11.03273 9.0750 13.5810 49.648 1000 a# Let's check the accuracy of the methods as well as their timings. For that

# we need to define a check function that takes as input a LIST with each slot

# representing the output of each method. The check must return TRUE or FALSE

check1 <- function (results) {

all(sapply(results[-1], function(x) {

max(abs(x - results[[1]]))

}) < 1e-15) # Compares all results pair-wisely with the first

}

# Example with check function

bench3 <- microbenchmark(

sweep(x = X, MARGIN = 2, STATS = mu, FUN = "-"),

t(apply(X, 1, function(x) x - mu)),

scale(X, center = mu, scale = FALSE),

{for (j in 1:m) Y4[, j] <- X[, j] - mu[j]; Y4},

t(t(X) - mu),

check = check1

)

bench3## Unit: microseconds

## expr min

## sweep(x = X, MARGIN = 2, STATS = mu, FUN = "-") 25.066

## t(apply(X, 1, function(x) x - mu)) 23.126

## scale(X, center = mu, scale = FALSE) 30.813

## { for (j in 1:m) Y4[, j] <- X[, j] - mu[j] Y4 } 1815.583

## t(t(X) - mu) 5.258

## lq mean median uq max neval cld

## 31.5470 39.70874 36.8125 44.3345 126.228 100 a

## 28.2165 37.77894 33.2445 44.9965 155.791 100 a

## 37.8560 51.20647 44.7735 57.8750 126.247 100 a

## 1874.4285 2199.84572 1976.6860 2171.4360 16726.024 100 b

## 6.8515 10.44978 9.1005 12.9015 34.804 100 aQuick animations with manipulate

The manipulate package (works only within RStudio!) allows to easily create simple animations. It is a simpler, local, alternative to Shiny applications.

library(manipulate)

# A simple example

manipulate({

plot(1:n, sin(2 * pi * (1:n) / 100), xlim = c(1, 100), ylim = c(-1, 1),

type = "o", xlab = "x", ylab = "y")

lines(1:100, sin(2 * pi * 1:100 / 100), col = 2)

}, n = slider(min = 1, max = 100, step = 1, ticks = TRUE))# Illustrating several types of controls using the kernel density estimator

manipulate({

# Sample data

if (newSample) {

set.seed(sample(1:1000))

} else {

set.seed(12345678)

}

samp <- rnorm(n = n, mean = 0, sd = 1.5)

# Density estimate

plot(density(x = samp, bw = h, kernel = kernel),

xlim = c(-x.rang, x.rang)/2, ylim = c(0, y.max))

# Show data

if (rugSamp) {

rug(samp)

}

# Add reference density

if (realDensity) {

tt <- seq(-x.rang/2, x.rang/2, l = 200)

lines(tt, dnorm(x = tt, mean = 0, sd = 1.5), col = 2)

}

},

n = slider(min = 1, max = 250, step = 5, initial = 10),

h = slider(0.05, 2, initial = 0.5, step = 0.05),

x.rang = slider(1, 10, initial = 6, step = 0.5),

y.max = slider(0.1, 2, initial = 0.5, step = 0.1),

kernel = picker("gaussian", "epanechnikov", "rectangular",

"triangular", "biweight", "cosine", "optcosine"),

rugSamp = checkbox(TRUE, "Show rug"),

realDensity = checkbox(TRUE, "Draw real density"),

newSample = button("New sample!")

)# Another example: rotating 3D graphs without using rgl

# Mexican hat

x <- seq(-10, 10, l = 50)

y <- x

f <- function(x, y) {r <- sqrt(x^2 + y^2); 10 * sin(r)/r}

z <- outer(x, y, f)

# Colors

nrz <- nrow(z)

ncz <- ncol(z)

zfacet <- z[-1, -1] + z[-1, -ncz] + z[-nrz, -1] + z[-nrz, -ncz]

col <- viridis(100)

facetcol <- cut(zfacet, length(col))

col <- col[facetcol]

# 3D plot

manipulate(

persp(x, y, z, theta = theta, phi = phi, expand = 0.5, col = col,

ticktype = "detailed", xlab = "X", ylab = "Y", zlab = "Sinc(r)"),

theta = slider(-180, 180, initial = 30, step = 5),

phi = slider(-90, 90, initial = 30, step = 5))Handling big data in R

The ff and ffbase packages

R stores all the data in RAM, which is where all the processing takes place. But when the data does not fit into RAM (e.g., vectors of size $2\times 10^9$), alternatives are needed. ff is an R package for working with data that does not fit in RAM. From ff’s description:

The

ffpackage provides data structures that are stored on disk but behave (almost) as if they were in RAM by transparently mapping only a section (pagesize) in main memory - the effective virtual memory consumption perffobject.

The package ff lacks some standard statistical methods for operating with ff objects. These are provided by ffbase.

Let’s see an example.

# Not really "big data", but for the sake of illustration

set.seed(12345)

n <- 1e6

p <- 10

beta <- seq(-1, 1, length.out = p)^5

# Data for linear regression

x1 <- matrix(rnorm(n * p), nrow = n, ncol = p)

x1[, p] <- 2 * x1[, 1] + rnorm(n, sd = 0.1)

x1[, p - 1] <- 2 - x1[, 2] + rnorm(n, sd = 0.5)

y1 <- 1 + x1 %*% beta + rnorm(n)

bigData1 <- data.frame("resp" = y1, "pred" = x1)

# Data for logistic regression

x2 <- matrix(rnorm(n * p), nrow = n, ncol = p)

y2 <- rbinom(n = n, size = 1, prob = 1 / (1 + exp(-(1 + x2 %*% beta))))

bigData2 <- data.frame("resp" = y2, "pred" = x2)

# Sizes of objects

print(object.size(bigData1), units = "Mb")## 83.9 Mbprint(object.size(bigData2), units = "Mb")## 80.1 Mb# Save files to disk to emulate the situation with big data

write.csv(x = bigData1, file = "bigData1.csv", row.names = FALSE)

write.csv(x = bigData2, file = "bigData2.csv", row.names = FALSE)

# Read files using ff

library(ffbase) # Imports ff

bigData1ff <- read.table.ffdf(file = "bigData1.csv", header = TRUE, sep = ",")

bigData2ff <- read.table.ffdf(file = "bigData2.csv", header = TRUE, sep = ",")

# Recall: the *.csv are not copied into RAM!

print(object.size(bigData1ff), units = "Kb")## 38.6 Kbprint(object.size(bigData2ff), units = "Kb")## 38.7 Kb# Delete the csv files in disk

file.remove(c("bigData1.csv", "bigData2.csv"))## [1] TRUE TRUEOperations on ff objects are carried out similarly as with regular data.frames:

# Operations on ff objects "almost" as with regular data.frames

class(bigData1ff)## [1] "ffdf"class(bigData1ff[, 1])## [1] "numeric"bigData1ff[1:5, 1] <- rnorm(5)

# See ?ffdf for more allowed operations

# Filter of data frames

ffwhich(bigData1ff, bigData1ff$resp > 5)## ff (open) integer length=12943 (12943)

## [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8]

## 32 86 341 377 437 440 688 747 :

## [12936] [12937] [12938] [12939] [12940] [12941] [12942] [12943]

## 999645 999720 999724 999780 999825 999833 999845 999885Regression using biglm and friends

The richness of information returned by R’s lm has immediate drawbacks when working with big data (large $n$, $n>p$). An example is the following. If $n=10^8$ and $p=10$, simply storing the response and the predictors takes up to $8.2$ Gb in RAM. This is in the edge of feasibility for many regular laptops. However, calling lm will consume, at the very least, $16.5$ Gb merely storing the residuals, effects, fitted.values, and qr decomposition. Although there are more efficient ways of performing linear regression in base R (e.g., with .lm.fit), we still need to rethink the least squares estimates computation (takes $\mathcal{O}(np+p^2)$ in memory) to do not overflow the RAM.

A handy solution is given by the biglm package, which allows to fit a generalized linear model (glm) in R consuming much less RAM. Essentially, we have two possible approaches for fitting a glm:

-

Use a regular

data.frameobject to store the data, then usebiglmto fit the model. This assumes that:- We are able to store the dataset in RAM or, alternatively, that we can split it into chunks that are fed into the model iteratively, updating the fit via

udpatefor each new data chunk. - The updating must rely only in the new chunk of data, not in the full dataset (otherwise, there is no point in chunking the data). This is possible with linear models, but not possible (at least exaclty) for generalized linear models.

- We are able to store the dataset in RAM or, alternatively, that we can split it into chunks that are fed into the model iteratively, updating the fit via

-

Use a

ffdfobject to store the data, then useffbase’sbigglm.ffdfto fit the model.

We will focus on the second approach due to its simplicity. For an example of the use of the first approach with a linear model, see here.

Let’s see first an example of linear regression.

library(biglm)

# bigglm.ffdf has a very similar syntax to glm - but the formula interface does

# not work always as expected:

# bigglm.ffdf(formula = resp ~ ., data = bigData1ff) # Does not work

# bigglm.ffdf(formula = resp ~ pred.1 + pred.2, data = bigData1ff) # Does work,

# but not very convenient for a large number of predictors

# Hack for automatic inclusion of all the predictors

f <- formula(paste("resp ~", paste(names(bigData1ff)[-1], collapse = " + ")))

# bigglm.ffdf's call

biglmMod <- bigglm.ffdf(formula = f, data = bigData1ff, family = gaussian())

class(biglmMod)## [1] "bigglm" "biglm"# lm's call

lmMod <- lm(formula = resp ~ ., data = bigData1)

# The reduction in size of the resulting object is more than notable

print(object.size(biglmMod), units = "Kb")## 46.7 Kbprint(object.size(lmMod), units = "Mb")## 358.6 Mb# Summaries

s1 <- summary(biglmMod)

s2 <- summary(lmMod)

s1## Large data regression model: bigglm(formula = f, data = bigData1ff, family = gaussian())

## Sample size = 1e+06

## Coef (95% CI) SE p

## (Intercept) 1.0021 0.9939 1.0104 0.0041 0.0000

## pred.1 -0.9732 -1.0132 -0.9332 0.0200 0.0000

## pred.2 -0.2866 -0.2911 -0.2821 0.0022 0.0000

## pred.3 -0.0535 -0.0555 -0.0515 0.0010 0.0000

## pred.4 -0.0041 -0.0061 -0.0021 0.0010 0.0000

## pred.5 -0.0002 -0.0022 0.0018 0.0010 0.8398

## pred.6 0.0003 -0.0017 0.0023 0.0010 0.7740

## pred.7 0.0026 0.0006 0.0046 0.0010 0.0090

## pred.8 0.0521 0.0501 0.0541 0.0010 0.0000

## pred.9 0.2840 0.2801 0.2880 0.0020 0.0000

## pred.10 0.9867 0.9667 1.0066 0.0100 0.0000s2##

## Call:

## lm(formula = resp ~ ., data = bigData1)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -4.8798 -0.6735 -0.0013 0.6735 4.9060

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 1.0021454 0.0041200 243.236 < 2e-16 ***

## pred.1 -0.9732675 0.0199989 -48.666 < 2e-16 ***

## pred.2 -0.2866314 0.0022354 -128.227 < 2e-16 ***

## pred.3 -0.0534834 0.0009997 -53.500 < 2e-16 ***

## pred.4 -0.0040772 0.0009984 -4.084 4.43e-05 ***

## pred.5 -0.0002051 0.0009990 -0.205 0.83731

## pred.6 0.0002828 0.0009989 0.283 0.77706

## pred.7 0.0026085 0.0009996 2.610 0.00907 **

## pred.8 0.0520744 0.0009994 52.105 < 2e-16 ***

## pred.9 0.2840358 0.0019992 142.076 < 2e-16 ***

## pred.10 0.9866851 0.0099876 98.791 < 2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 0.9993 on 999989 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.5777, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5777

## F-statistic: 1.368e+05 on 10 and 999989 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16# The summary of a biglm object yields slightly different significances for the

# coefficients than for lm. The reason is that biglm employs N(0, 1)

# approximations for the distributions of the t-tests instead of the exact

# t distribution. Obviously, if n is large, the differences are inappreciable.

# Extract coefficients

coef(biglmMod)## (Intercept) pred.1 pred.2 pred.3 pred.4

## 1.002111877 -0.973211105 -0.286614434 -0.053495479 -0.004083508

## pred.5 pred.6 pred.7 pred.8 pred.9

## -0.000201877 0.000286831 0.002610137 0.052073260 0.284048419

## pred.10

## 0.986656286# AIC

AIC(biglmMod, k = 2)## [1] 998702.4# Prediction works "as usual"

predict(biglmMod, newdata = bigData1[1:5, ])## [,1]

## 1 2.459090

## 2 2.797450

## 3 1.446842

## 4 1.601357

## 5 2.153806# newdata must contain a column for the response!

# predict(biglmMod, newdata = bigData2[1:5, -1]) # Error

# Update the model with more training data - this is key for chunking the data

update(biglmMod, moredata = bigData1[1:100, ])## Large data regression model: bigglm(formula = f, data = bigData1ff, family = gaussian())

## Sample size = 1000100Model selection of biglm models can be done with the leaps package. This is achieved by the regsubsets function, which returns the best subset of up to (by default) nvmax = 8 predictors. The function requires the full biglm model to begin the “exhaustive” search, in which is crucial the linear structure of the estimator.

# Model selection adapted to big data models

library(leaps)

reg <- regsubsets(biglmMod, nvmax = p, method = "exhaustive")

plot(reg) # Plot best model (top row) to worst model (bottom row). Black color

# means that the predictor is included, white stands for excluded predictor

# Get the model with lowest BIC

subs <- summary(reg)

subs$which## (Intercept) pred.1 pred.2 pred.3 pred.4 pred.5 pred.6 pred.7 pred.8

## 1 TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

## 2 TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

## 3 TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

## 4 TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

## 5 TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE

## 6 TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE

## 7 TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE

## 8 TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE

## 9 TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE

## pred.9 pred.10

## 1 FALSE TRUE

## 2 TRUE TRUE

## 3 TRUE TRUE

## 4 TRUE TRUE

## 5 TRUE TRUE

## 6 TRUE TRUE

## 7 TRUE TRUE

## 8 TRUE TRUE

## 9 TRUE TRUEsubs$bic## [1] -558597.7 -837849.2 -854049.3 -856882.0 -859573.4 -861924.3 -861927.2

## [8] -861920.2 -861906.5subs$which[which.min(subs$bic), ]## (Intercept) pred.1 pred.2 pred.3 pred.4 pred.5

## TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE

## pred.6 pred.7 pred.8 pred.9 pred.10

## FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUEAn example of logistic regression:

# Same comments for the formula framework - this is the hack for automatic

# inclusion of all the predictors

f <- formula(paste("resp ~", paste(names(bigData2ff)[-1], collapse = " + ")))

# bigglm.ffdf's call

bigglmMod <- bigglm.ffdf(formula = f, data = bigData2ff, family = binomial())

# glm's call

glmMod <- glm(formula = resp ~ ., data = bigData2, family = binomial())

# Compare sizes

print(object.size(bigglmMod), units = "Kb")## 173.1 Kbprint(object.size(glmMod), units = "Mb")## 679.2 Mb# Summaries

s1 <- summary(bigglmMod)

s2 <- summary(glmMod)

s1## Large data regression model: bigglm(formula = f, data = bigData2ff, family = binomial())

## Sample size = 1e+06

## Coef (95% CI) SE p

## (Intercept) 0.9960 0.9906 1.0015 0.0027 0.0000

## pred.1 -0.9970 -1.0028 -0.9911 0.0029 0.0000

## pred.2 -0.2839 -0.2890 -0.2789 0.0025 0.0000

## pred.3 -0.0533 -0.0583 -0.0483 0.0025 0.0000

## pred.4 -0.0015 -0.0065 0.0035 0.0025 0.5466

## pred.5 -0.0020 -0.0070 0.0030 0.0025 0.4201

## pred.6 0.0029 -0.0021 0.0079 0.0025 0.2465

## pred.7 0.0035 -0.0015 0.0085 0.0025 0.1584

## pred.8 0.0529 0.0479 0.0579 0.0025 0.0000

## pred.9 0.2821 0.2770 0.2871 0.0025 0.0000

## pred.10 0.9962 0.9903 1.0021 0.0029 0.0000s2##

## Call:

## glm(formula = resp ~ ., family = binomial(), data = bigData2)

##

## Deviance Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.5073 -0.8193 0.4306 0.7691 3.0466

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) 0.996049 0.002707 367.986 <2e-16 ***

## pred.1 -0.996951 0.002931 -340.134 <2e-16 ***

## pred.2 -0.283919 0.002535 -112.021 <2e-16 ***

## pred.3 -0.053271 0.002496 -21.340 <2e-16 ***

## pred.4 -0.001504 0.002494 -0.603 0.547

## pred.5 -0.002011 0.002494 -0.806 0.420

## pred.6 0.002889 0.002493 1.159 0.246

## pred.7 0.003519 0.002495 1.411 0.158

## pred.8 0.052924 0.002495 21.216 <2e-16 ***

## pred.9 0.282086 0.002531 111.466 <2e-16 ***

## pred.10 0.996187 0.002933 339.625 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 1265999 on 999999 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 974224 on 999989 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 974246

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 5# AIC

AIC(bigglmMod, k = 2)## [1] 974246.3# Prediction works "as usual"

predict(bigglmMod, newdata = bigData2[1:5, ], type = "response")## [,1]

## 1 0.4330916

## 2 0.9237983

## 3 0.2420483

## 4 0.9619891

## 5 0.5443102# predict(bigglmMod, newdata = bigData2[1:5, -1]) # ErrorASCII fun in R

Text-based graphs with txtplot

When evaluating R in a terminal with no possible graphical outputs (e.g. in a supercomputing cluster), it may be of usefulness to, at least, visualize some simple plots in a rudimentary way. This is what the txtplot and the NostalgiR package do, by means of ASCII graphics that are equivalent to some R functions.

R graph |

ASCII analogue |

|---|---|

plot |

txtplot |

boxplot |

txtboxplot |

barplot(table()) |

txtbarchart |

curve |

txtcurve |

acf |

txtacf |

plot(density()) |

nos.density |

hist |

nos.hist |

plot(ecdf()) |

nos.ecdf |

qqnorm(); qqline() |

nos.qqnorm |

qqplot |

nos.qqplot |

contour |

nos.contour |

image |

nos.image |

Let’s see some examples.

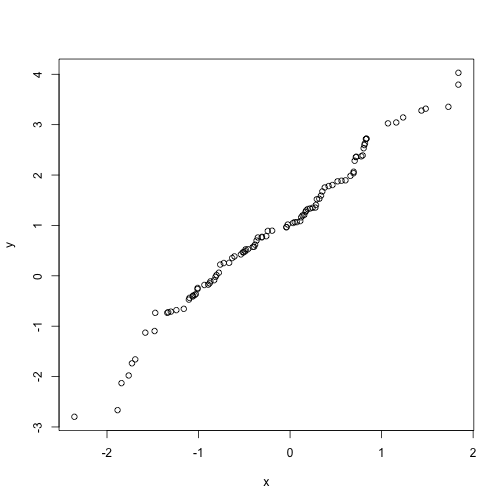

library(txtplot) # txt* functions

# Generate common data

x <- rnorm(100)

y <- 1 + x + rnorm(100, sd = 1)

let <- as.factor(sample(letters, size = 1000, replace = TRUE))

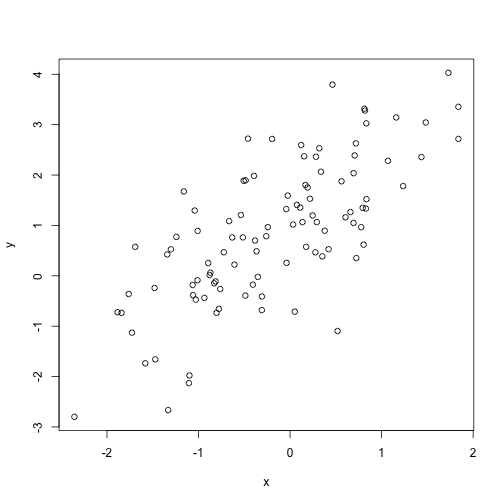

# txtplot

plot(x, y)

txtplot(x, y)## +------+-----------+-----------+-----------+-----------++

## 4 + * * +

## | * * * * |

## | * * *** * * |

## 2 + ** * * ** * * +

## | ** * **** * * * |

## | * * * ** * * **** *** |

## | * * *** * * * **** ** |

## 0 + * * ***** *** +

## | ** ** * * * |

## | * * |

## -2 + * * +

## | * * |

## +------+-----------+-----------+-----------+-----------++

## -2 -1 0 1 2# txtboxplot

boxplot(x, horizontal = TRUE)

txtboxplot(x)## -2 -1 0 1 2

## |------+-----------+-----------+------------+-----------+-|

## +-------+-------+

## ------------------| | |-----------------

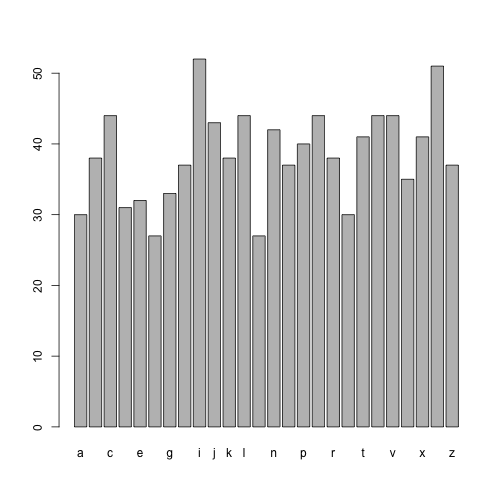

## +-------+-------+# txtbarchart

barplot(table(let))

txtbarchart(x = let)## ++---------+---------+----------+---------+---------+----+

## 5 + * * +

## | * * * * * * * * |

## 4 + * * * * * * * * * * * * +

## | * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * |

## 3 + * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * +

## | * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * |

## 2 + * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * +

## | * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * |

## 1 + * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * +

## | * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * |

## 0 + * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * +

## ++---------+---------+----------+---------+---------+----+

## 0 5 10 15 20 25

## Legend:

## 1=a, 2=b, 3=c, 4=d, 5=e, 6=f, 7=g, 8=h, 9=i, 10=j, 11=k, 12=

## l, 13=m, 14=n, 15=o, 16=p, 17=q, 18=r, 19=s, 20=t, 21=u, 22=

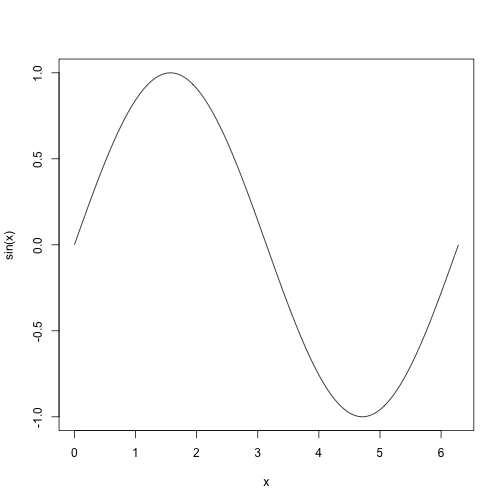

## v, 23=w, 24=x, 25=y, 26=z# txtcurve

curve(expr = sin(x), from = 0, to = 2 * pi)

txtcurve(expr = sin(x), from = 0, to = 2 * pi)## +-+-------+-------+-------+-------+------+-------+----+

## 1 + ********* +

## | *** *** |

## | ** ** |

## 0.5 + ** ** +

## | ** ** |

## | * * |

## 0 + * ** ** +

## | ** ** |

## -0.5 + ** * +

## | ** ** |

## | *** *** |

## -1 + ********* +

## +-+-------+-------+-------+-------+------+-------+----+

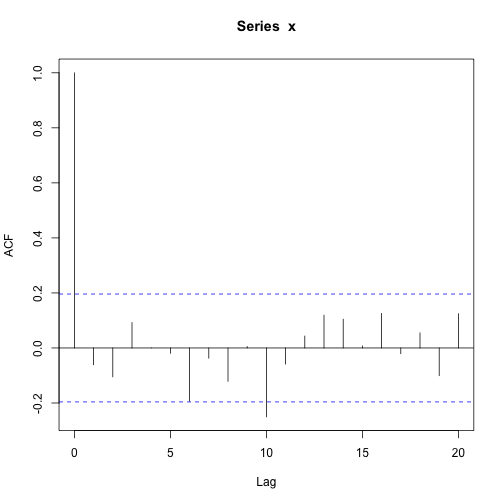

## 0 1 2 3 4 5 6# txtacf

acf(x)

txtacf(x)## +-+------------+-----------+-----------+-----------+--+

## 1 + * +

## | * |

## 0.8 + * +

## 0.6 + * +

## | * |

## 0.4 + * +

## | * |

## 0.2 + * +

## | * * * * * * |

## 0 + * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * +

## | * * * * * * * |

## -0.2 + * * +

## +-+------------+-----------+-----------+-----------+--+

## 0 5 10 15 20library(NostalgiR) # nos.* functions

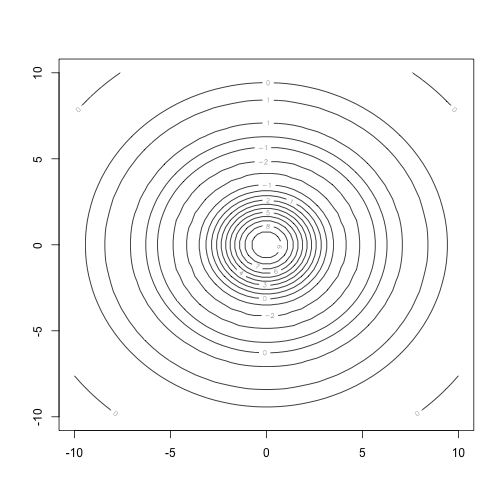

# Mexican hat

xx <- seq(-10, 10, l = 50)

yy <- xx

f <- function(x, y) {r <- sqrt(x^2 + y^2); 10 * sin(r)/r}

zz <- outer(xx, yy, f)

# nos.density

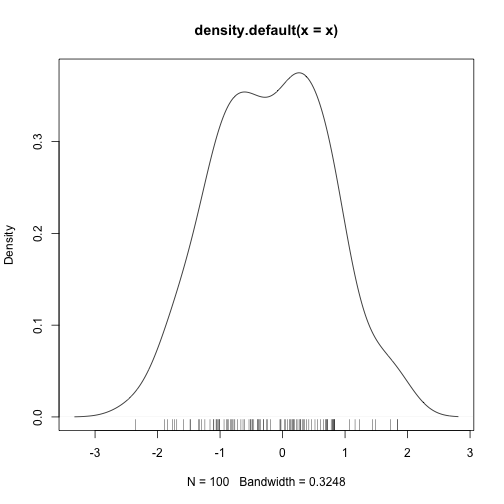

plot(density(x)); rug(x)

nos.density(x)## +----+-------+-------+------+-------+-------+-------++

## | ~~~~~~~~~~~~ |

## | ~~ ~~ |

## 0.3 + ~~ ~~ +

## D | ~~ ~ |

## e | ~~ ~ |

## n 0.2 + ~~ ~~ +

## s | ~~ ~ |

## i | ~~ ~~ |

## t 0.1 + ~~ ~~~ +

## y | ~~~ ~~~ |

## | ~~~ ~~~~ |

## 0 + ~~~~~~~~~ oooooooooooooooooooooo oo o oo ~~~~~~ +

## +----+-------+-------+------+-------+-------+-------++

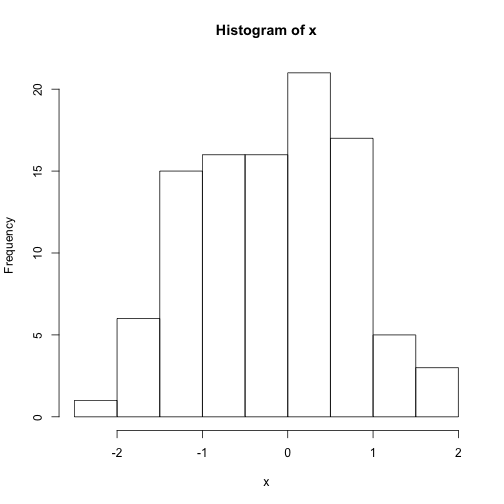

## -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3# nos.hist

hist(x)

nos.hist(x)## +-----+-----------+-----------+-----------+-----------+

## 20 + o +

## | o |

## F | o o o o |

## r 15 + o o o o o +

## e | o o o o o |

## q | o o o o o |

## u 10 + o o o o o +

## e | o o o o o |

## n | o o o o o o |

## c 5 + o o o o o o o +

## y | o o o o o o o o |

## 0 + o o o o o o o o o +

## +-----+-----------+-----------+-----------+-----------+

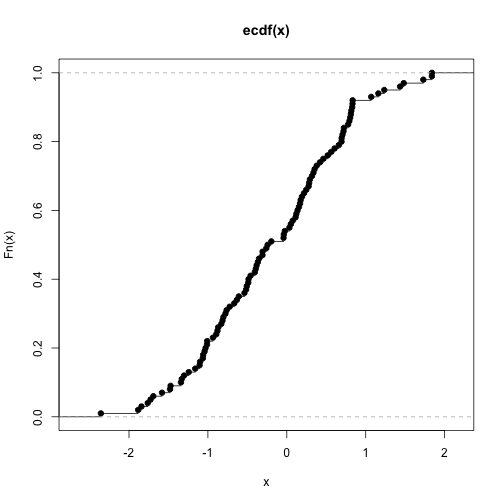

## -2 -1 0 1# nos.ecdf

plot(ecdf(x))

nos.ecdf(x)## +-----+-----------+----------+-----------+----------++

## 1 + ooo~o~~oo +

## | oo~~~ |

## 0.8 + oooo +

## | ooo |

## E 0.6 + ooo +

## C | o~ooo |

## D | ooo |

## F 0.4 + oooo +

## | oooo |

## 0.2 + ooo +

## | ooooo |

## | o~~~~~ooooo~ |

## 0 +-----+-----------+----------+-----------+----------++

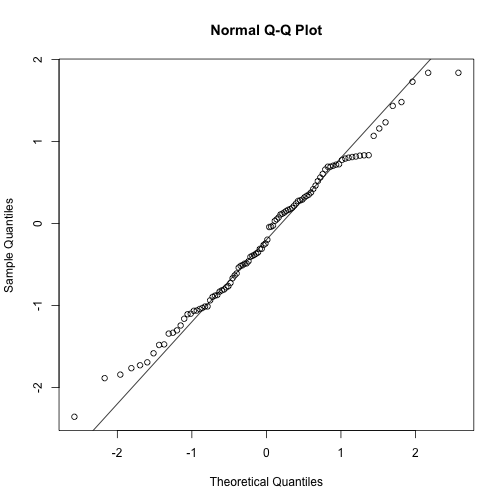

## -2 -1 0 1 2# nos.qqnorm

qqnorm(x); qqline(x)

nos.qqnorm(x)## 2 +-------+--------+---------+--------+---------+-------+

## | o~o~o o |

## S | ~ooo~ |

## a 1 + oooooo +

## m | oooo~ |

## p 0 + oooooo +

## l | ~ooo~ |

## e | ~ooooo |

## -1 + oooooo +

## Q | ~oooo |

## s | o o~ooo |

## -2 + o ~~~~~ +

## +-------+--------+---------+--------+---------+-------+

## -2 -1 0 1 2

## Theoretical Qs# nos.qqplot

qqplot(x, y)

nos.qqplot(x, y)## +------+-----------+-----------+-----------+-----------++

## 4 + o +

## | ooo oo o |

## | oo |

## 2 + oooo ~ +

## | oooo ~~~~~~~ |

## | ooo ooo ~~~~~~~ |

## | ooooo ~~~~~~~ |

## 0 + oooo ~~~~~~~~ +

## | o ooo~~~~~~~ |

## | oo~~~~~ |

## -2 + ~~~~~oo +

## | o o |

## +------+-----------+-----------+-----------+-----------++

## -2 -1 0 1 2# nos.contour

contour(xx, yy, zz)

nos.contour(data = zz, xmin = min(xx), xmax = max(xx),

ymin = min(yy), ymax = max(yy))## +-+------------+-----------+------------+-----------+--+

## 10 + 33 22 22222 3333333333 22222 222 33 +

## | 33332222222233333444444444444443333322222222333 |

## | 333222 222333444444 444444333222 22233 |

## | 222222333444 444444444444444444 444333222222 |

## 5 + 2 22233444 44443333222222222233334444 4443322 2 +

## | 2 3344 444332 1111111111111111 233444 4433 2 |

## | 22 3 44 44332111112345555554321111123344 44 3 2 |

## | 3 44 4332 111134555 555431111 2334 4433 |

## | 3 4 4 32 111 245 542 11 2344 4 3 |

## 0 + 3 4 4 32 111 245 542 11 2344 4 3 +

## | 3 44 4332 111134555 555431111 2334 4433 |

## | 22 3 44 43322111112345555554321111122344 44 3 2 |

## | 2233344 444332111111111111111111233444 4433322 |

## -5 + 2 22233444 44443332222111122223334444 4443322 2 +

## | 222222333444 444444444444444444 444333222222 |

## | 333222 222333444444 444444333222 22233 |

## | 3333222 22223333344444444444444333332222 222333 |

## -10 + 33 222 22222 3333333333 22222 2222 33 +

## +-+------------+-----------+------------+-----------+--+

## -10 -5 0 5 10

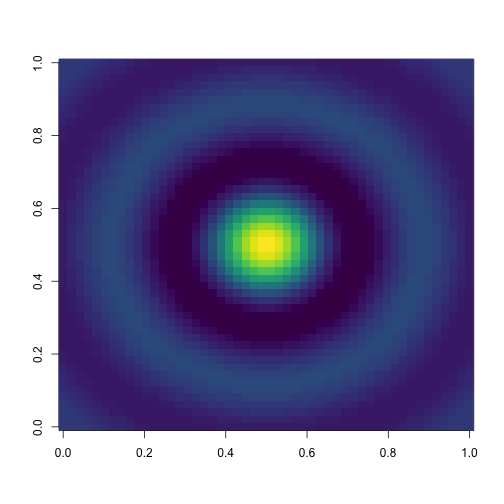

## Legend: 1 ~ -2.02; 2 ~ -0.769; 3 ~ -0.082; 4 ~ 0.795; 5 ~ 1.74# nos.image

image(zz, col = viridis(50))

nos.image(data = zz, xmin = min(xx), xmax = max(xx),

ymin = min(yy), ymax = max(yy))## +-+------------+-----------+------------+-----------+--+

## 10 + o oooo........................................ooooo +

## | o oo....................oooo....................ooo |

## | . .............oooooooooooooooooooooo.............. |

## | . .........oooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo.......... |

## 5 + . ......oooooooooo................oooooooooo....... +

## | . ....oooooooo........................oooooooo..... |

## | . ...oooooooo..........................oooooooo.... |

## | . ..ooooooo..........oooxxxxooo..........ooooooo... |

## | . ..oooooo.........ooxXX####XXxoo.........oooooo... |

## 0 + . .ooooooo........ooxXX######XXxoo........ooooooo.. +

## | . ..ooooooo........ooxxXXXXXXxxoo........ooooooo... |

## | . ..oooooooo..........oooooooo..........oooooooo... |

## | . ...oooooooo..........................oooooooo.... |

## -5 + . .....oooooooo......................oooooooo...... +

## | . .......ooooooooooo............ooooooooooo........ |

## | . ..........oooooooooooooooooooooooooooo........... |

## | o ...............oooooooooooooooooo...............o |

## -10 + o ooo..........................................oooo +

## +-+------------+-----------+------------+-----------+--+

## -10 -5 0 5 10

## Legend:

## . ~ (-2.17,0.235); o ~ (0.235,2.64); x ~ (2.64,5.05); X ~ (5

## .05,7.45); # ~ (7.45,9.86)Cute animals with cowsay

cowsay is a package for printing messages with ASCII animals. Although it has little practical use, it is way fun! There is only one function, say, that produces an animal with a speech bubble.

library(cowsay)

# Random fortune

set.seed(363)

say("fortune", by = "random")##

## -----

## If 'fools rush in where angels fear to tread', then Bayesians 'jump' in where frequentists fear to 'step'.

## Charles C. Berry

## about Bayesian model selection as an alternative to stepwise regression

## R-help

## November 2009

## ------

## \

## \

## \

## , ,

## /( )`

## \ \___ / |

## /- _ `-/ '

## (/\/ \ \ /\

## / / | `

## O O ) / |

## `-^--'`< '

## (_.) _ ) /

## `.___/` /

## `-----' /

## <----. __ / __ \

## <----|====O)))==) \) /====

## <----' `--' `.__,' \

## | |

## \ /

## ______( (_ / \______

## ,' ,-----' | \

## `--{__________) \/ [nosig]# All animals

# sapply(names(animals), function(x) say(x, by = x))

# Annoy the users of your package with good old clippy

say(what = "It looks like you\'re writing a letter!",

by = "clippy", type = "warning")## Warning in say(what = "It looks like you're writing a letter!", by = "clippy", :

##

## -----

## It looks like you're writing a letter!

## ------

## \

## \

## __

## / \

## | |

## @ @

## || ||

## || ||

## |\_/|

## \___/ GB# A message from Yoda

say("Participating in the Coding Club UC3M you must. Yes, hmmm.", by = "yoda")##

##

##

## -----

## Participating in the Coding Club UC3M you must. Yes, hmmm.

## ------

## \

## \

## ____

## _.' : `._

## .-.'`. ; .'`.-.

## __ / : ___\ ; /___ ; \ __

## ,'_ ""--.:__;".-.";: :".-.":__;.--"" _`,

## :' `.t""--.. '<@.`;_ ',@>` ..--""j.' `;

## `:-.._J '-.-'L__ `-- ' L_..-;'

## "-.__ ; .-" "-. : __.-"

## L ' /.------.\ ' J

## "-. "--" .-"

## __.l"-:_JL_;-";.__

## .-j/'.; ;"""" / .'\"-.

## .' /:`. "-.: .-" .'; `.

## .-" / ; "-. "-..-" .-" : "-.

## .+"-. : : "-.__.-" ;-._ \

## ; \ `.; ; : : "+. ;

## : ; ; ; : ; : \:

## ; : ; : ;: ; :

## : \ ; : ; : ; / ::

## ; ; : ; : ; : ;:

## : : ; : ; : : ; : ;

## ;\ : ; : ; ; ; ;

## : `."-; : ; : ; / ;

## ; -: ; : ; : .-" :

## :\ \ : ; : \.-" :

## ;`. \ ; : ;.'_..-- / ;

## : "-. "-: ; :/." .' :

## \ \ : ;/ __ :

## \ .-`.\ /t-"" ":-+. :

## `. .-" `l __/ /`. : ; ; \ ;

## \ .-" .-"-.-" .' .'j \ / ;/

## \ / .-" /. .'.' ;_:' ;

## :-""-.`./-.' / `.___.'

## \ `t ._ / bug

## "-.t-._:'

##